Marjorie Kelly & Wealth Supremacy

January 3, 2024 – John Abrams

Matt Kenyon

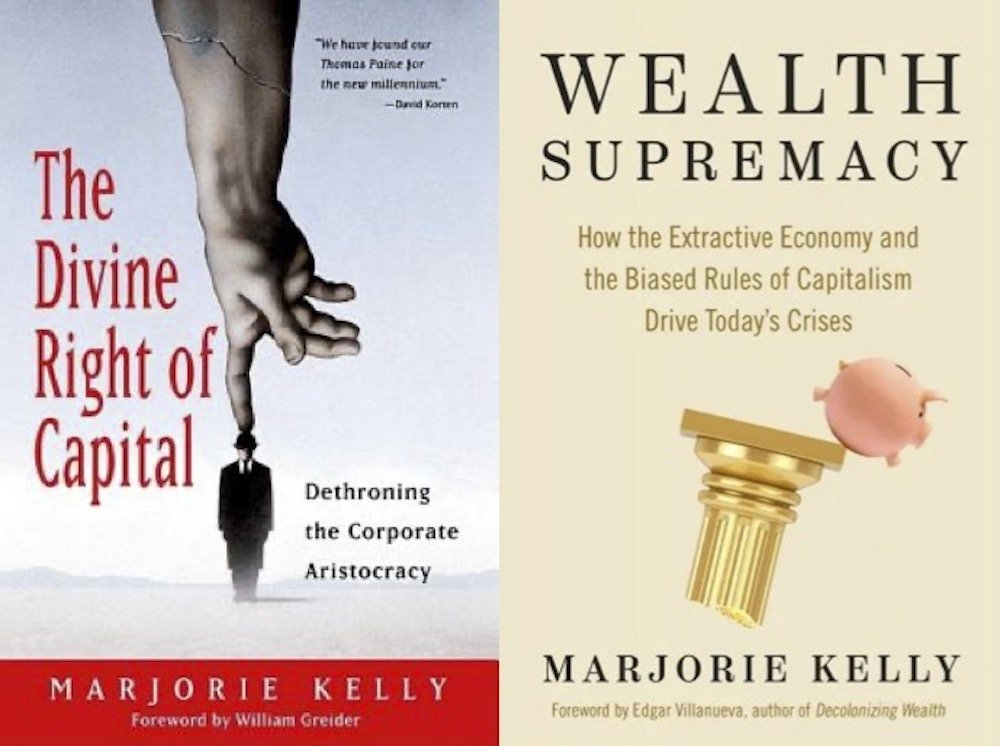

Marjorie Kelly is one of the people whose thinking has influenced my career most profoundly. For 20 years, from 1987 to 2007, she published Business Ethics Magazine. I read it cover-to-cover each month. In 2003, Marjorie published The Divine Right of Capital, in which she explains our lopsided economic system in stark terms and offers solutions for redesigning corporations and companies in a way that serves us all.

Jay Coen-Gilbert, one of the three cofounders of B Corp (the rigorous ethical business certification program that now includes about 8,000 companies worldwide) says that Marjorie’s book was the inspiration for the B Corp movement, which intends to make business a force for good.

It inspired me too.

Marjorie is an important author, but she is also an activist and consummate convener. She assembles groups of people to think together about how to democratize the economy. I have been involved in several of these events. The most recent was in 2019, when she and colleagues at The Democracy Collaborative (where she is Distinguished Senior Fellow) brought together 50 companies which are both employee-owned and certified B Corps (including South Mountain Company). After that gathering, Fast Company headlined this article about it, “The Business of the Future is Ethical, Sustainable, and Employee-Owned.”

Marjorie’s latest book, released this fall, is Wealth Supremacy, a bold manifesto that identifies excess concentrated wealth as “the driving force behind the multiple global crises we face today.”

“Wealth grows through extraction,” she says. “The 1 percent don’t ‘create wealth.’ They extract it . . . from the pockets of ordinary people, our common government, and the planet – sapping the resilience of society.”

There is an evolving thread that runs through Marjorie’s major books: The Divine Right of Capital, Owning Our Future (2012), The Making of a Democratic Economy (with Ted Howard, 2019), and now Wealth Supremacy. Together, they provide the fundamental thinking that underlies everything I am hoping to communicate to the millions of retiring founders of small businesses in my forthcoming book Founder to Future: New Strategies for Impact, Equity, and Succession (to be published spring 2025).

It’s the idea, quite simply, of sharing privilege.

Reading Wealth Supremacy reminded me of the privilege with which I grew up (and with which I live) and the first time I began to viscerally understand it. It was in 1970 when I moved, with a few others, to a small rural community in Southern Oregon, an area that had been dependent on the lumber industry for more than 100 years. Once the prime forests were decimated, the lumber companies packed up, shuttered the mills, left the locals without a livelihood, and stripped away their identity (a pattern that extractive industries repeat over and over).

And then we arrived – young refugees-by-choice from privilege. For the locals, we represented, with our thirst for the knowledge and skills of rural self-sufficiency, an opportunity to reclaim their identity (if not their livelihood) because they had these skills in abundance to share.

That fall, several of us went to work for an impoverished family who scratched out a living making firewood and fence posts from the waste the lumber companies had left behind. The family had to drive their goods 45 miles to Grants Pass and sell them for next-to-nothing. Henry was the family patriarch who ran the show. Along with his son Marvin, a neighbor named Jerry worked with him too. The first day Henry brought us to work, Jerry, put off by our long hair, refused to shake hands. But, working together side-by-side over time, Jerry took pride in sharing his know-how and we became great friends. Less than a year later, when we had decided to leave the area, Jerry offered to give us half his land (half of everything he had) if we’d stay.

The fact that we could choose to return to privilege, and Jerry had no options beyond his hardscrabble life, was an injustice not lost on me. In fact, it defined my life going forward – it pushed me to share wealth and power in business and to help those less fortunate when I can. Jerry’s willingness to share the only privilege he had was an unforgettable lesson.

Marjorie tells how hard it is to overcome the difference between those born with privilege and those born without. Her skillful storytelling and colorful language makes it easier to understand stuff that we wish we didn’t have to learn but know we must.

She says that our economic system determines that wealthy people matter more than others and that they can claim a limitless right to extract from the rest of us. And she suggests that “moral capitalism” is as impossible as “moral racism.” The solution is system change – evolving beyond capitalism and socialism to a fully democratic economy and society.

As Marjorie says, “When the stock market falls 20 or 30 percent, headlines blare the news. Meanwhile, the number of insects worldwide has fallen an estimated 75 percent over fifty years, and this went unnoticed for decades. Insects are not assets of DuPont; industrial chemicals are. Since many 401(k) plans and institutional portfolios hold DuPont shares, we’re implicitly hoping the value of chemical assets will increase as we hope for these portfolios to rise. The insect apocalypse is designed in.”

New designs are necessary; the old ones aren’t working. Mandy Cabot, owner of one of the 50 companies brought together by The Democracy Collaborative, is committed to the new.

Mandy is the founder of Dansko and cofounder of Silk Grass Farms in Belize. She says, “The Divine Right of Capital was transformative to my thinking as an entrepreneur: what is the purpose of any business if not to improve the lives of everyone it touches? This was the spark that ignited our decision to transfer ownership of Dansko to our employees. Wealth Supremacy deepens our resolve to imagine a new paradigm, reversing decades of extraction in Belize by giving the land and its resources back to the people in trust and creating a regenerative agribusiness to support it.”

When I was doing research for my book Companies We Keep in 2004, I found a small cadre of people promoting employee ownership. Twenty years later, I find a tremendously expanded infrastructure of people and organizations working relentlessly to bring widespread employee ownership and new corporate design approaches into mainstream practice and policy.

This progress gives me hope. Thank you, Marjorie, for helping us craft new foundations for the democratic economy. Wealth Supremacy will push us forward.

Happy 2024 and Peace to All. Time to stand up and right this listing ship.